During the German occupation, Abruzzo and Lazio were part of the so-called “Belt of Rome”, and the provinces of these two regions, lying immediately behind the front, depended directly on the local army corps commands. Most of the manpower was used for the construction of the Gustav-Bernhardt line and for other activities useful to the Nazi army.

The war needs, transport difficulties, the hostility of the local population and boycotting by some local authorities meant that only a few thousand workers from these areas were sent to work in the Third Reich.

In Abruzzo and Lazio, the recruitment and assistance of most workers was dealt with by the General Inspectorate of Labour (IGL).

The Inspectorate had been established in October 1943 by the Ministry of National Defence, which would then be renamed, on 6 January the following year, Ministry of the Armed Forces, and it would consequently take the new name of Military Inspectorate of Labour (IML).

On 16 September 1943, Field Marshal Keitel, head of the Supreme Command of the Wehrmacht (OKW), sent Kesselring the order to transfer to northern Italy “the able-bodied male population of the area under his command, preferably from large cities”. This last caveat applied in particular to the cities of Naples and Rome. In order to acquire manpower, Kesselring was authorised to use “any appropriate measures”, including “hostage taking” and the publication of appeals to the population. In the event of resistance, he could also intervene using force against the Italian police, who would be “held liable for such actions”. According to the principle, later widespread, that “German soldiers fight, and the Italians work for them”, enlisted men did not need to be forced to provide military service.

Also due to the counterproductive experience of forced roundups implemented by the Wehrmacht in the Naples and Rome areas, the German authorities initially tried to recruit workers without using coercive measures.

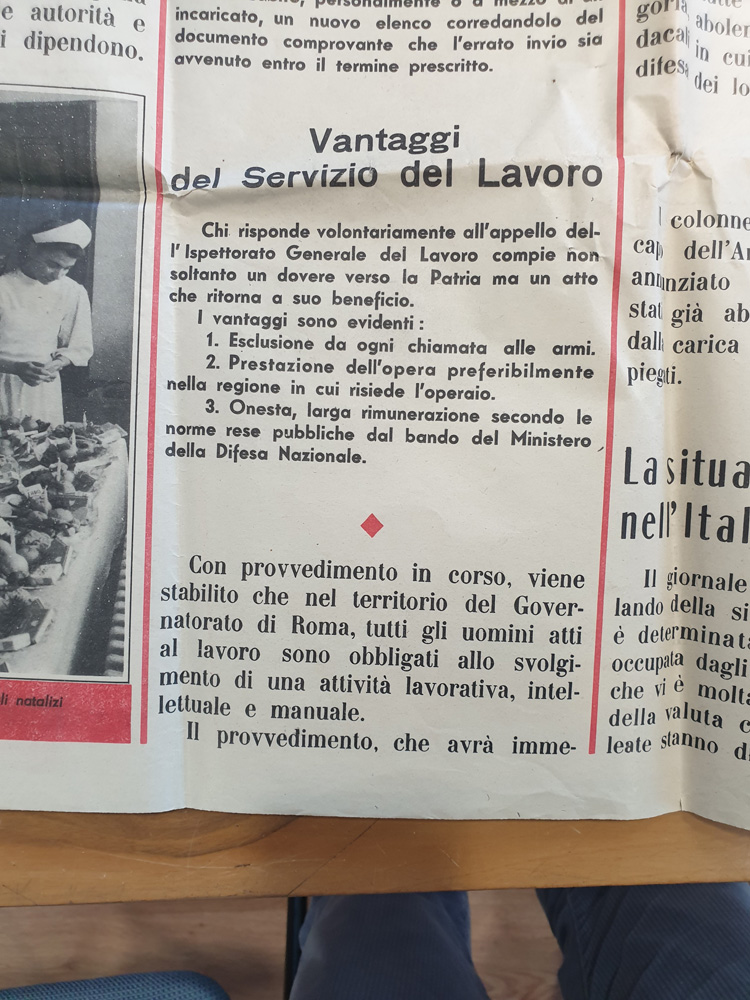

The German authorities thought that the favourable recruitment terms would prompt several thousand people to voluntarily respond to the appeal. These optimistic predictions had been fuelled by information provided by the Roman Federation of the Republican Fascist Party, who stated that in Rome alone there were 100,000 unemployed and over half a million people living in a state of poverty. Nevertheless, the first voluntary enrolment campaign for the Reich ended in complete failure, resulting in only about a thousand applications.

To force Romans to report to the employment offices, the German authorities ordered the withdrawal of ration cards by 15 January 1944, under the motto “work to eat”. The measure was difficult to apply and not very effective, both due to the many duplicate copies in circulation and due to the black market, which often met the population’s food needs. For the same reasons, and also because of the hostility of the population, attempts to list job dodgers in Rome also failed.

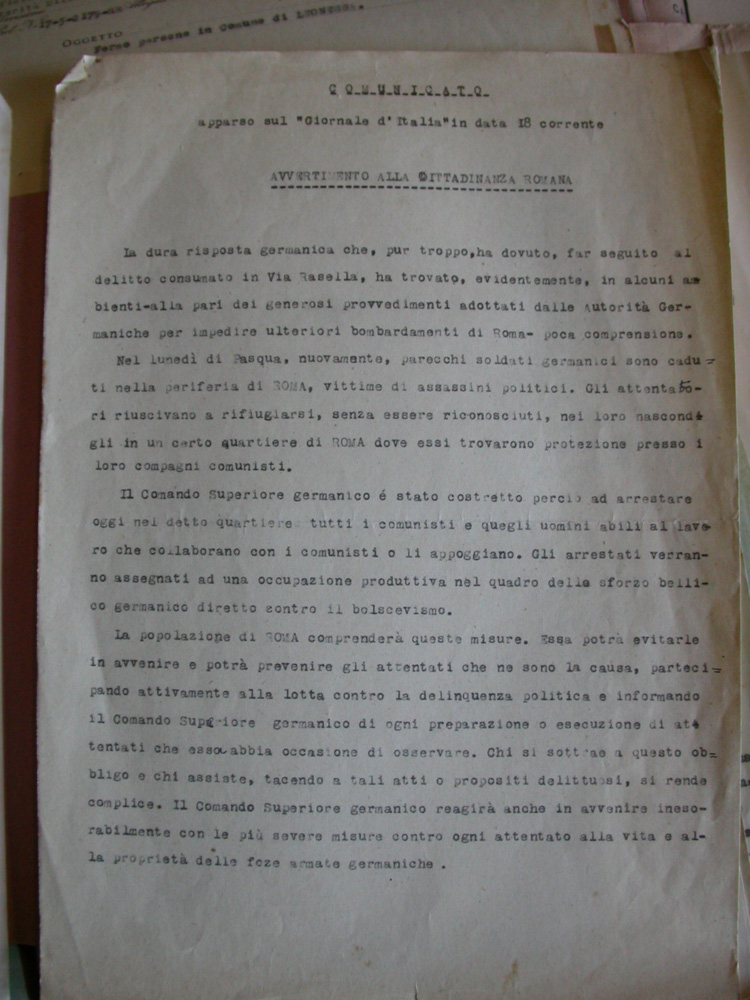

Given the poor results of voluntary enlistment, the German authorities, assisted by the Italian police, began to carry out the first roundups. The abduction of manpower in the capital and in Lazio involved police operations carried out by Rome’s police, led by Pietro Caruso, and by the Republican “bands”: Bardi-Pollastrini, Bernasconi and Koch.

In February 1944, the Germans ordered that anybody arrested by the Italian police in the city of Rome “should be taken, by the Police, to a concentration camp” where they would then be “picked up by the German Office for Compulsory Labour Service”.

In the same period, the “Centro raccolta sfollati della Breda”, which resembled a concentration camp, was operating in Rome. The facility housed over 5,000 displaced people who were subsequently moved to the nearby “workers’ village”, while the “Campo d’Internamento Tedesco ex Fabbrica Armi VII – Officine Ernesto Breda” remained under the supervision of some soldiers of the Italian African Police (PAI) and of the Wehrmacht. Under the supervision of the SS, deserters, anti-fascists and Jews were confined in this factory shed.

The only facility in the municipality of Rome that was specifically used as a place for the collection and sorting of forced labourers was the former POW camp set up in 1942 in Cinecittà. There, among others, over 700 people rounded up on 17 April 1944 in the Quadraro district were taken, and subsequently transferred to the Fossoli di Carpi camp. On 24 June, at least 500 of them signed a form which provided for their immediate release from the concentration camp “on condition that they report immediately to the GBA offices in Modena”. Shortly thereafter they would travel to Germany with the status of “free workers”, to be employed in the Reich war industry.

In the provinces of Littoria and Frosinone, most of the workers were used for on-site work, often with the active collaboration of local authorities. Instead, in the area of Rieti and Viterbo, the Nazi-Fascists managed to recruit some men for forced labour, above all with roundups and “anti-guerrilla” operations.

In the provinces of Abruzzo, the methods of recruiting workers were similar to those used in Lazio. Most of the workers were used for works along the Gustav line. The Italian Social Republic (RSI) authorities collaborated to supply the German forces above all with mechanics, blacksmiths, saddlers, upholsterers, tailors, cooks, carpenters, electricians and drivers.

Despite the relentless Italian Fascist propaganda in favour of voluntary recruitment, also in Abruzzo it failed to achieve the hoped-for success. Only a few workers signed up, both because they feared being sent to the Third Reich and because they were frightened by the violence used by the Nazis to control the territory. Furthermore, the possibility of crossing the front or hiding in the mountains made it easier for them to avoid being taken.

Most of the “battalions of workers” employed in the provinces of Chieti and L’Aquila would comprise rounded up displaced people and young men who had not reported when called up. Concentration camp internees were also deployed for fortification works on the front line and to carry out various services for the German army. In Teramo, in January 1944, a special concentration camp was set up, whose internees were also taken by the Nazi-Fascists to be used as forced labour.

THE HISTORIANS’ VIEW

During the German occupation, few workers were taken from Abruzzo and Lazio to be deported to the Third Reich.

The use of workers rounded up in the areas close to the Gustav Line.

The Italian Social Republic authorities also cooperated actively in the recruitment of manpower in the provinces of Abruzzo and Lazio.

The strategies implemented by the Nazi-Fascists to recruit manpower in Rome and Lazio.

Among the main roundups carried out by the Germans in Rome was that in Quadraro on 17 April 1944. The reasons for the roundup and the fate of the deportees.

by Costantino Di Sante