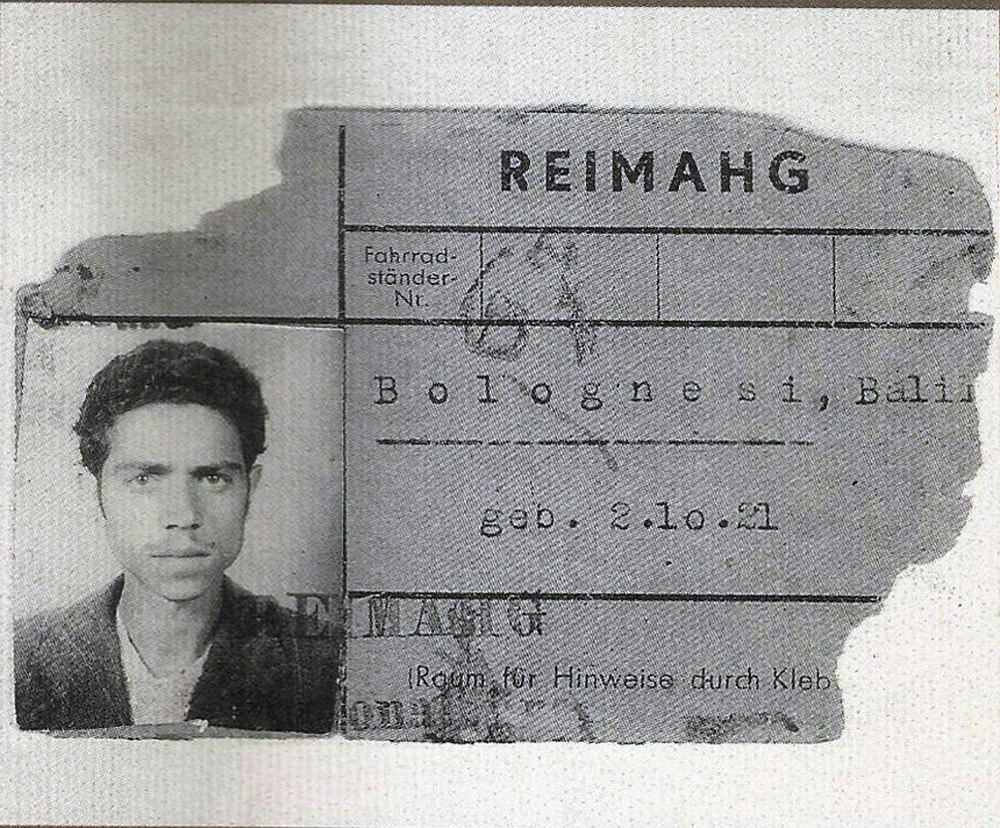

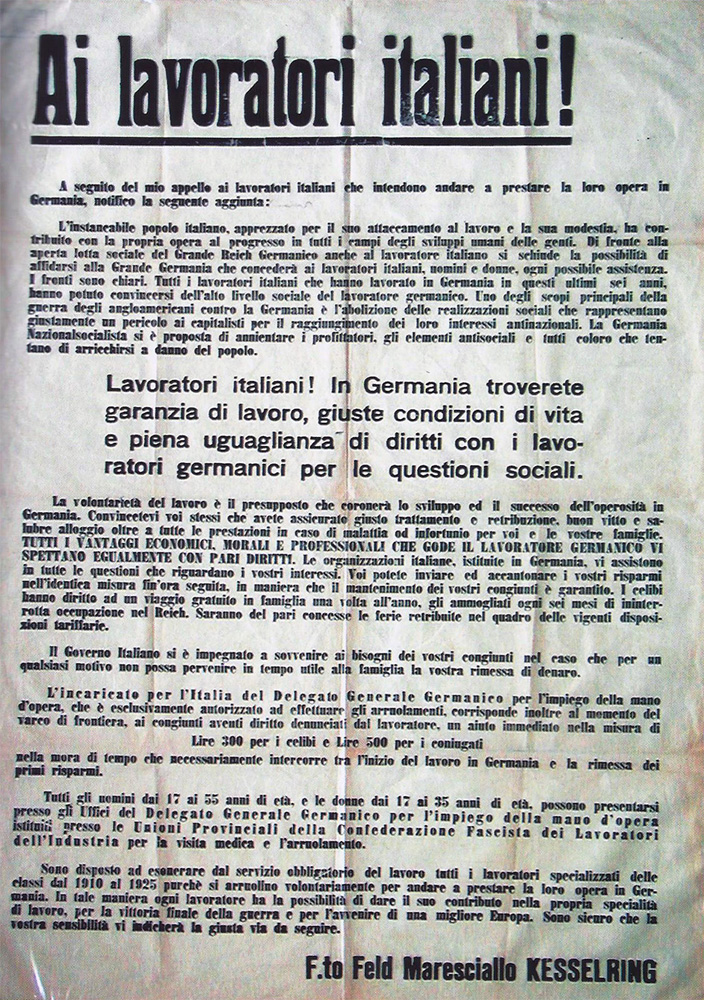

Since the territory of Marche was directly involved in the fighting, the interest of the German army group responsible for southern Italy concentrated on the use of auxiliaries and manpower for fortification and evacuation works, in particular those concerning the construction of the Gothic Line. This partly explains the relatively low numbers of workers sent from Marche to the Reich, since they were needed locally. Hand in hand with attempts at voluntary recruitment, the German authorities engaged in a series of roundups, often concomitant with those carried out by units of the Wehrmacht alongside Italian units, aimed at capturing partisans to use as manpower beyond the Brenner. This however ended up encouraging young people to try and avoid labour conscription orders by fleeing to the mountains, where they ended up swelling the ranks of the partisans. In this context, an important role was played by Militärkommandantur 1019, the local branch of the German administration in Italy. Already in its first report regarding the situation in Marche, it had clearly stated that the various attempts at forced recruitment by the troops in the operational area had encouraged the male population to flee to the mountains. The same report moreover admitted that the results of the recruitment campaign for Italian workers were very disappointing, so much so that the target of 12-14,000 workers to be sent from each province to the Reich, imposed by the labour division of the German administration in Italy, would never be achieved. According to the information that can be gleaned from the reports, it is clear that the German workforce recruitment campaign had an unsatisfying outcome in Marche. The roundup campaign by German troops that began in Marche in March 1944 should also be read from the perspective of finding manpower to send to Germany. Most of the workers abducted during these operations ended up working in Germany at the Reimahg firm in Kahla, responsible for building the Messerschmitt 262 (Me 262) jet fighter-interceptor. The story of Reimahg was intertwined with that of forced labourers from the Marche region, in particular from Macerata, who arrived in Kahla in April and May 1944 when fitting-out of the plants was scheduled. In April 1944, 187 Italians were already employed, but in all there were around 15,000 people from nine countries working on the project. It seems that among the approximately 10,000 forced labourers in Kahla in January 1945, the majority were Soviets (3,476 workers), with Italians close behind (3,178 workers). According to the most recent historiographical research (the studies of Marc Bartuschka), the number of workers who lost their lives in Kahla (including the period immediately following its liberation) was between 2,000 and 3,000, a much higher figure than the initial estimates, which spoke of 991, but certainly more reliable than the number of 6,000, based only on witness accounts, which appears on the memorial erected to their memory in Thuringia. Again according to Bartuschka’s studies, Italian deaths numbered between 750 and 1,000, that is between a quarter and a third of the total contingent from the country.

THE HISTORIANS’ VIEW

Voluntary recruitment and forced recruitment between the front and the Gothic Line.

Militärkommandantur 1019 and forced labour recruitment.

The central role of the Kahla camp for Macerata’s forced labourers.

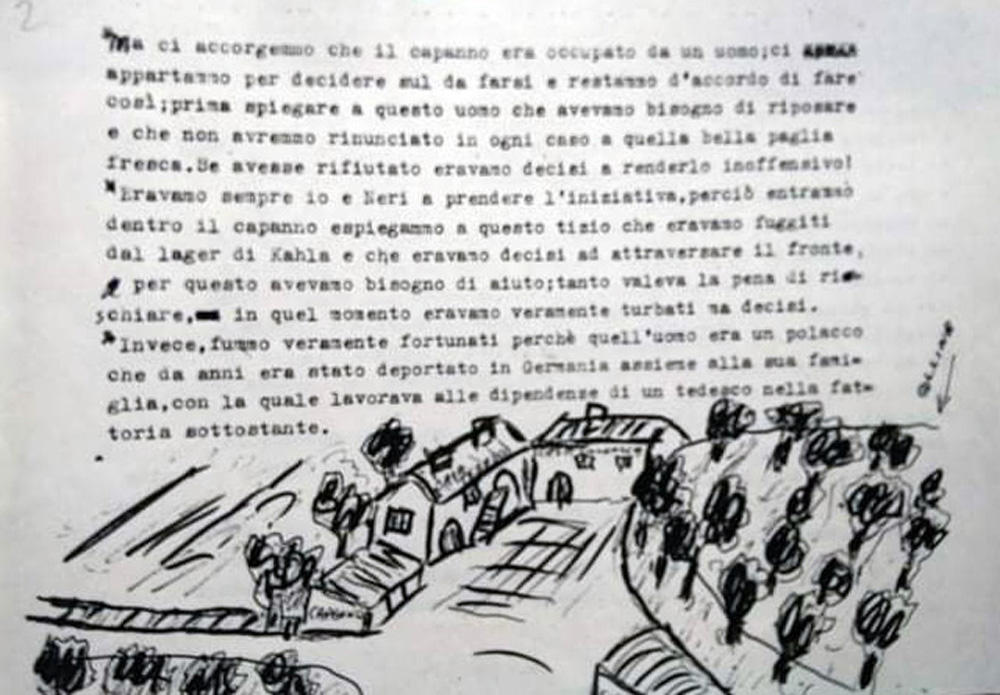

An exemplary tale: Balilla Bolognesi and his “Diaries of a deportee”.

by Annalisa Cegna