The German plans for a fighter jet, for which preliminary designs had already been drafted in 1939, intensified in 1943 when the logistically most suitable site for completion of the project was found near Kahla, in Thuringia. It became operational in July 1944. The construction of a complex including both industrial plants and housing for the staff was decided by Fritz Sauckel, who created the Reimahg (acronym for Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring) group and ordered that work “proceed as quickly as possible without scruples of any kind”. Between 11 April 1944 – when work began at the site – and liberation,…

Although the numbers of Italian civilians forced into working for the Third Reich were significant, their story was neglected in the public memory of post-fascist Italy. They were not even taken into consideration in the compensation measures for victims and the persecuted issued by the governments which had taken over in the Kingdom of the South and then in the Republic. Regarding the latter aspect, the decision to consider voluntariness as a discriminating factor was crucial: since it was impossible to assess who had accepted job offers for work in the Reich, and who instead had been the victim of…

Royal Decree Law no. 123 (published in Official Gazette no. 73 of 30/3/43) was issued on 30 March 1943, and laid down that “employees of the State Administrations and any citizen, who, not being in military service, are assigned, on the basis of mobilization papers, to commands, departments or services of the armed forces on land, sea and air mobilized by the respective general staffs, for war operations, assume the legal status of members of the military”. Militarization entailed subjection to military criminal law, i.e. to the rules of military discipline in force for the armed force to which the…

The whole arsenal of measures previously applied in occupied Europe (offers of attractive job contracts, conscription by age group, roundups in the countryside and raids in urban areas) was then implemented in Italy, in partly different ways depending on the areas specifically targeted. Operations originally conceived by the occupying forces primarily for other purposes, such as anti-partisan roundups or roundups aimed at moving the civilian population away from the territories behind the front, were also used to acquire manpower. By applying to Italy a practice that had already been in use for some time in Nazi Germany, the aim was…

The Monarcho-Fascist regime ruined any possibility of disengaging from the alliance with National Socialism between February and March 1940, when Benito Mussolini refused the British offer to supply Italy with the coal necessary for its economy, as German coal could no longer travel by sea due to the naval blockade imposed by London itself. Mussolini instead accepted Hitler’s proposal to transport over one million tons of coal a month entirely by land. At that point, Italy’s entry into the war was only a matter of time. However, things would not come to a head until the long crisis of 1943.…

Italy was the cradle of the Fascist political model, which was destined to gain popularity and spread beyond national borders after 1922. In Germany, the model was adopted, and implemented with extreme radicalism, from 1933 onwards. Although divided by conflicting interests of a geopolitical and economic nature regarding Austria in particular and the Balkan-Danubian region more generally, the Monarcho-Fascist and National-Socialist regimes could not fail to converge within a political project aimed at the destruction of the international framework and of the balance of power resulting from the Great War and the subsequent peace treaties. The Italian-German entente would start…

The migratory flow of Italian workers beyond the Brenner Pass in the years 1938-1942 originated in economic needs also linked to preparations for the future war, which required Germany to find a workforce to meet demand in every productive sector: from agriculture and industry to construction firms and mining companies. Germany was experiencing a period of strong economic recovery, after the crippling economic crisis of the years 1929-1932 which allowed Hitler and National Socialism to reach political power, and needed additional manpower. Italy, in the same period, was grappling with a problem that the regime had completely failed to solve:…

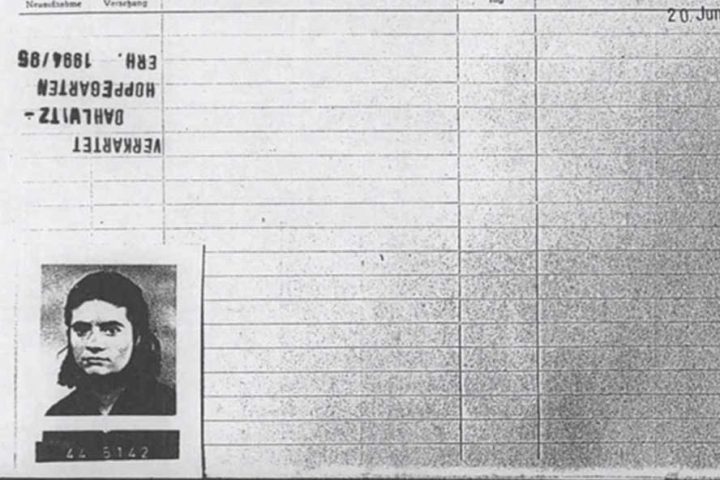

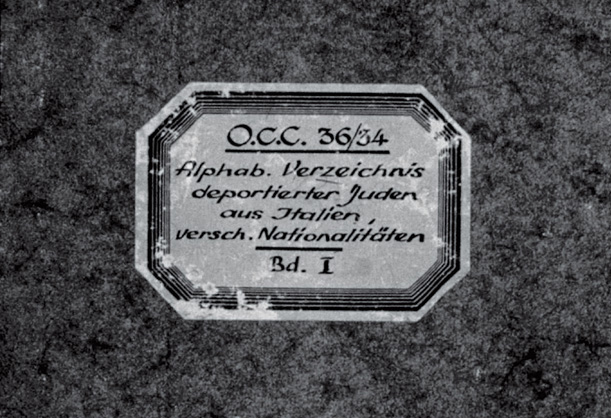

Finally, a third, numerically smaller group, comprising 40,517 people, according to currently available information, comprised those who were deported from Italy to the actual Nazi concentration camp system, run by the SS. It is appropriate to attribute the name of “deportees” solely to this group, thus restricting the meaning of the term “deportation” to that of “deportation to Nazi concentration and extermination camps”. This allows us to put every piece of the extremely complex overall puzzle – which brings together the experiences of the Italian men and women forcibly transferred to Germany following the armistice – in its right place.…

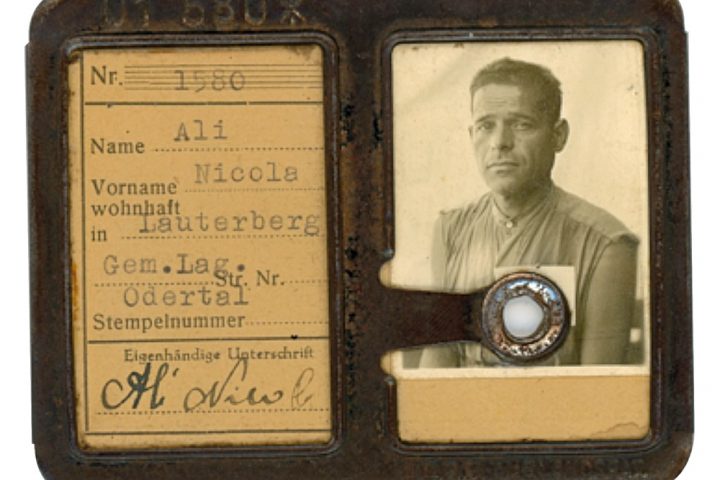

A second group, numbering about 100,000, included workers brought to Germany after 8 September 1943; a small number of them (a few thousand) had accepted job offers in the Reich advertised through propaganda by the offices opened in occupied Italy by the General Plenipotentiary for the Employment of Manpower (Generalbevollmächtigter für den Arbeitseinsatz, abbreviated to GBA), Fritz Sauckel, so in their case we cannot speak of direct coercion. Others, the absolute majority, were called up by post, in a way similar to that used for military service, or were enrolled as being eligible by age for military service, but also…

The largest group was made up of Internati Militari Italiani (Italian Military Internees, abbreviated as IMI), a term given by the military and political authorities of the Third Reich to officers, non-commissioned officers and soldiers of the armed forces of the Kingdom of Italy captured by the Wehrmacht in the days immediately following 8 September 1943, in the cities, southern France and the Balkans. By classifying them in this way, instead of – as required by international law – “prisoners of war” (Kriegsgefangenen), Berlin was able to deprive them of the protection of the International Red Cross (ICRC) in Geneva…