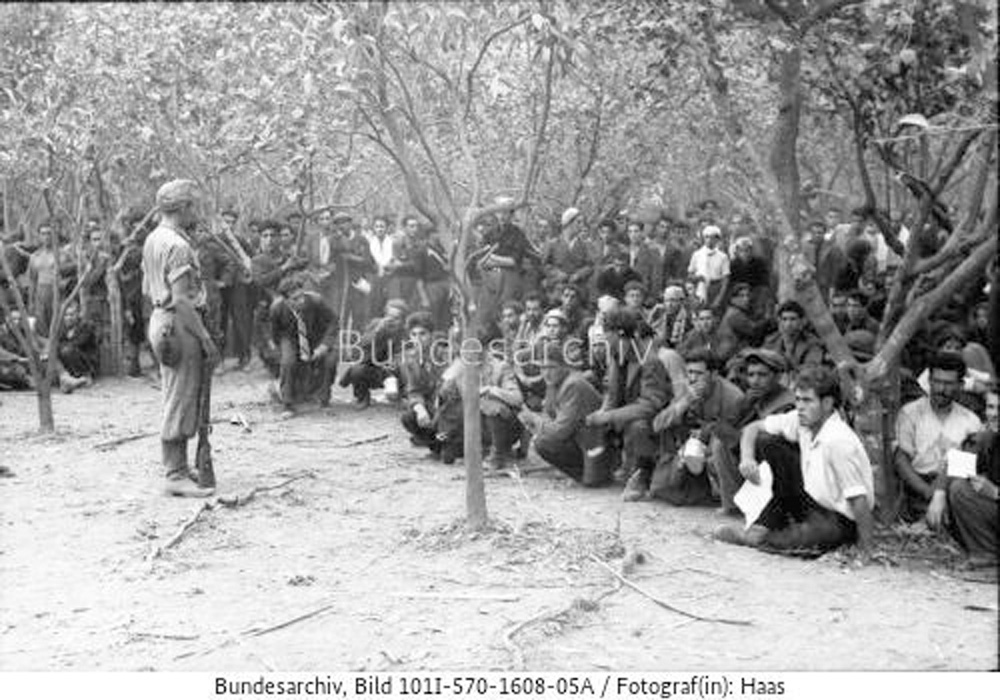

At dawn on 23 September 1943, the Wehrmacht launched in Campania what could be considered as the first but also the largest roundup of civilians in the entire period of occupation. In the space of a few days, according to German sources, almost 20,000 men were captured in the territory of what was then the province of Naples (today partly falling within the province of Caserta), with smaller numbers in the provinces of Benevento and Salerno, and also in a strip of Southern Lazio between Gaeta, Formia, Minturno and Castelforte.

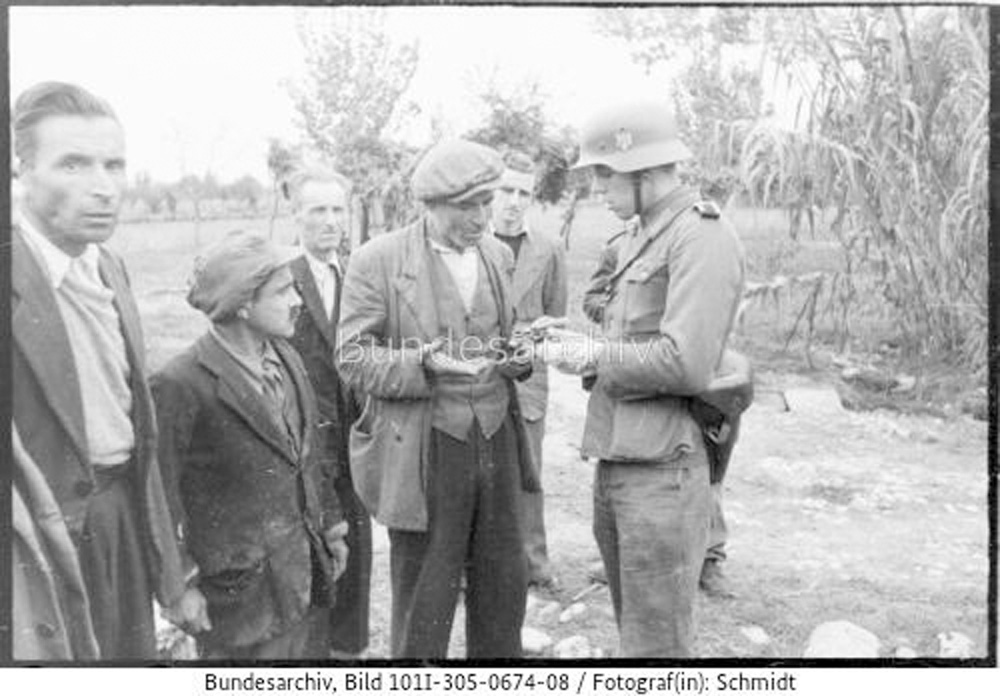

The rounding up of men took place alongside operations to leave “scorched earth” in front of the advancing Allied troops – until a few days previously still surrounded at the bridgehead of Salerno –, in view of a retreat of the German forces towards new defensive lines further north. The provisions issued by the German supreme command envisaged not only the removal of machinery, raw materials, and foodstuffs, but also the destruction of civil and industrial infrastructures, and the capture of all able-bodied men of working age, between 18 and 43 years of age (born between 1900 and 1925), to be sent to work in the Reich or employed locally.

The German divisions involved had been ordered to set up the main collection camps at Formia, Sparanise, and Maddaloni, later joined by Gaeta and Frosinone.

Carefully prepared, the roundups of men simultaneously struck a multitude of small and very small towns, where the local authorities had been ordered to gather men “capable of carrying arms and working” in the main squares, while German patrols surrounded the town and went from house to house.

In the urban area of Naples, the roundup did not begin until 27 September, and immediately led to the capture of many hundreds of men, but had to be interrupted due to popular resistance, in what would later become known as “le quattro giornate”, the four days. In the meantime, thousands more had been captured in the surrounding towns, such as Castellammare di Stabia, where the “slave hunt”, as the Germans often called it, proved particularly fruitful.

Some of those rounded up were detained for hard labour behind the front, while others managed to escape from collection centres and during transfers; many thousands were loaded onto the railway convoys headed for the Brenner Pass. After a few days of travelling, crammed into freight wagons and with few provisions, the detainees arrived at two main destinations in Bavaria: the Dachau KL and the military prison camp of Memmingen, Stalag VII B. In both places, most of them stayed only a few days, before being transferred to work destinations mainly located in Bavaria and Austria. However, some groups of people rounded up in Campania were sent to Saxony and Lower Saxony. They were used above all in industrial companies involved in the production of armaments, such as Messerschmitt, BMW, MAN, Hermann-Göring-Werke, and HASAG, but there were also groups assigned to chemical plants, explosives factories and ammunitions depots, mines and construction companies, river shipbuilding, and the railway sector, as well as agricultural, forestry and service companies.

THE HISTORIANS’ VIEW

The roundup methods used in Campania on 23 September 1943.

The role of the Dachau KL and of the Memmingen Stalag in the distribution of workers rounded up in Campania arriving in the autumn of 1943.

by Andrea Ferrari