The recruitment of manpower for Germany from Emilia during the two-year period 1943-1945 assumed a wide variety of forms.

In the province of Modena, where in the previous five years the bilateral pacts signed between Italy and Germany had seen large numbers of individual workers or peasant families move beyond the Alps due to unemployment, this tradition of peasant emigration to the Reich positively affected, at least initially, public attitudes to the recruitment plans adopted by the Fascist authorities after 8 September 1943.

The organisation of conscription, implemented through the mediation of the Fascist trade organisation (Fascist Provincial origanization of Farmers), and the massive influx up to March 1944 of workers called up by post, has similarities with the case of the neighbouring province of Mantua. This area was also characterised by massive peasant emigration to the Reich between 1938 and 1943 and, not surprisingly, during the period of the Italian Social Republic it was chosen as the site for the main collection camp for agricultural workers destined for transfer to Germany, according to the recruitment plans laid out by Marchiandi, the National Labour Commissioner. The German and Italian Social Republic officials, responsible for the labour offices in the province of Modena, in fact adopted recruitment methods aimed at finding manpower based on economic incentives and on the meticulous quantification of the surplus workforce in the area. They achieved appreciable results, at least during the early months of 1944, with the Provincial Organization of Agricultural Workers of Modena quantifying the total number of recruits at 8,168 on 10 March 1944.

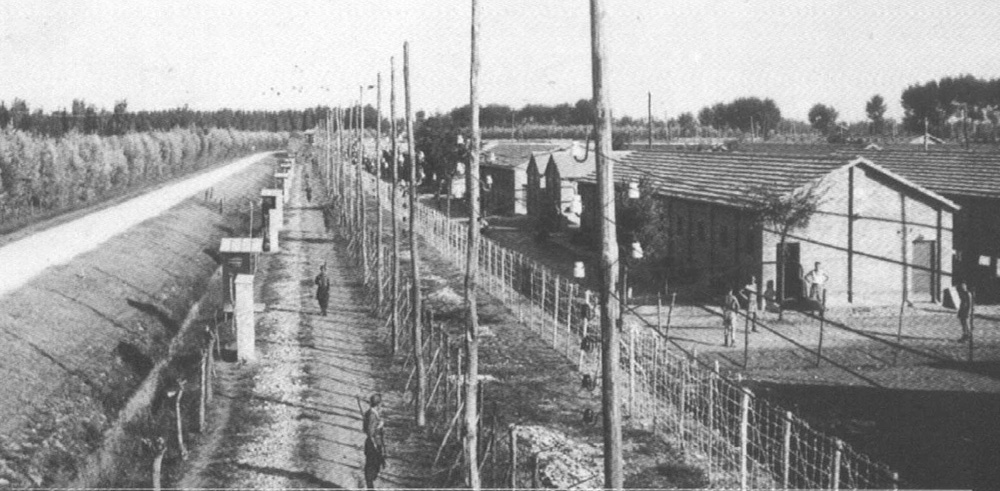

On the contrary, in the rest of Emilia the numbers of workers recruited for Germany only began to rise significantly when strategies based on the use of force and the threat of violent coercive methods were introduced. The recruitment of manpower for the Reich in the province of Bologna was strongly conditioned by its function, from spring 1944 onwards, as the main collection and selection hub for those rounded up from the frontline areas, from the regions of central Italy and from the territories crossed by the Gothic Line, concentrated in the “Caserme Rosse” camp in Via Corticella. Conscription in the province of Reggio Emilia was, on the one hand, characterised by agreements for the forced transfer of skilled workers signed between local representatives of the Reichsministerium für Rüstung und Kriegsproduktion (RMRK, Ministry for armaments and war production) and the management of Officine Meccaniche Italiane Reggiane, the only important industrial plant in an area with mainly agricultural production; on the other, it was linked to the mass roundups carried out in the mountain areas during the summer of 1944.

The large-scale counter-guerrilla military operations, primarily aimed at identifying partisan bands and those thought to be providing help to the armed Resistance, in fact also proved to be functional in selecting large contingents of able-bodied men to be forcibly assigned to work in Italy and the Reich. The three phases of the Wallenstein operation, implemented by German military forces in collaboration with Fascist armed units in the provinces of Piacenza, Parma, Reggio Emilia and Modena between 30 June and the early days of August 1944, took the overall form of a vast anti-partisan operation in defence of the Apennine passes, accompanied by the systematic abduction of the male population between 15 and 55 years of age, both for preventive purposes and to acquire manpower necessary for the wartime economy of the Nazi regime.

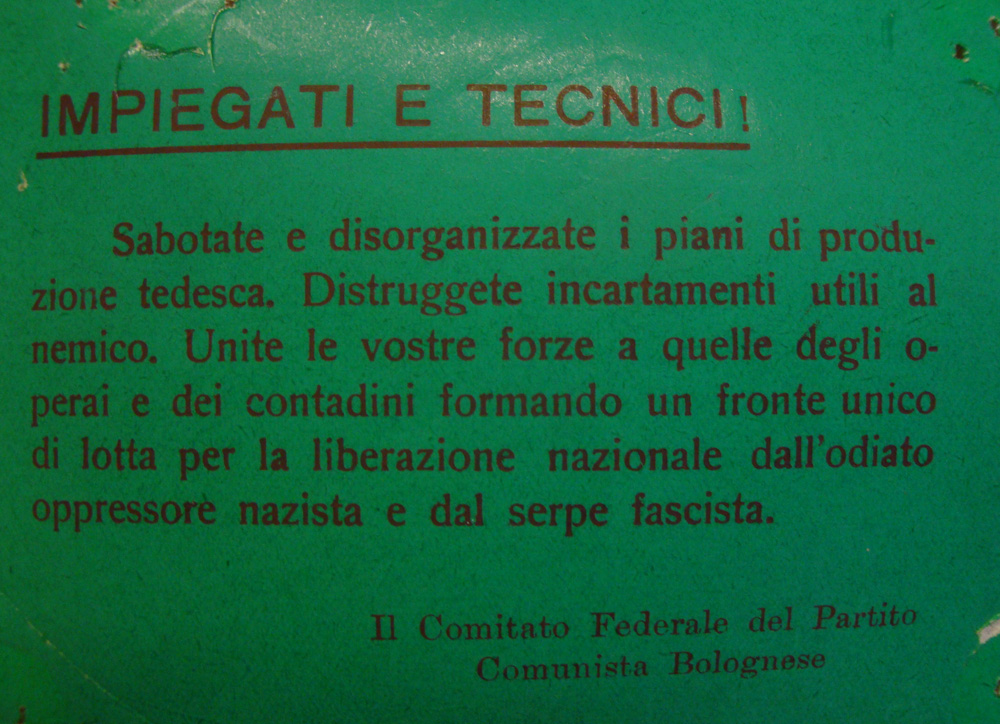

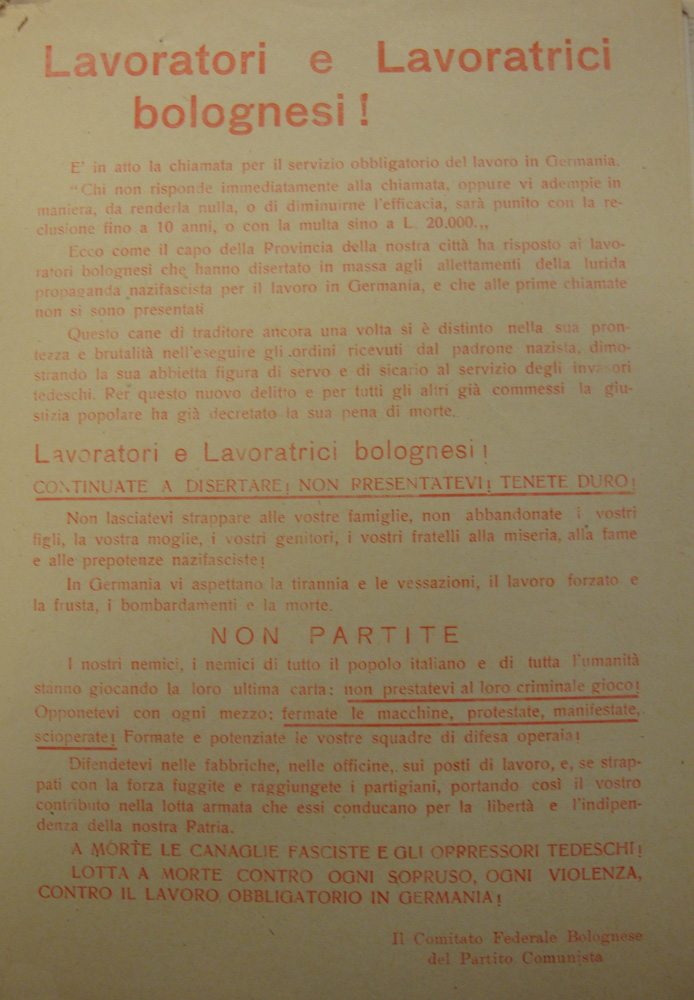

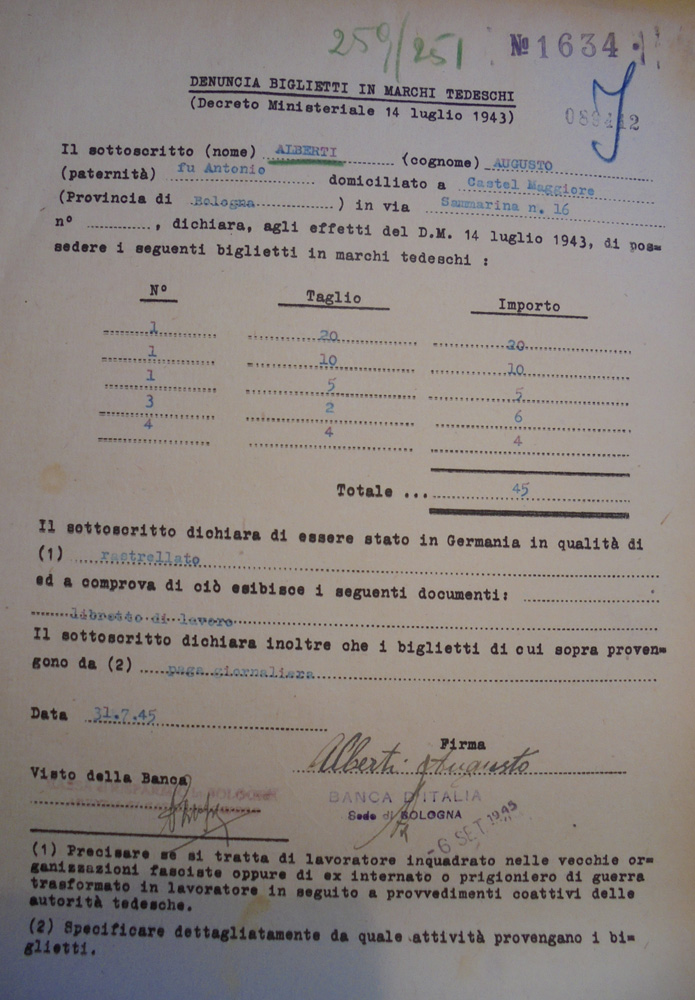

Until May 1944, the recruitment of manpower for the Reich proved to be inadequate to meet the targets set by the German authorities for the region, with the range of strategies adopted in Emilia between October 1943 and June 1944 proving to be mainly ineffective. According to a report drawn up by the German police offices, prior to May 1944, only 3593 industrial workers were sent across the Alps from the region, including 630 women (694 of the recruits came from the province of Bologna, 400 from Modena, 558 from Reggio Emilia, and 655 from Parma). Although, until the summer of 1944, there were still cases of workers or families voluntarily turning up at German manpower recruitment centres (run by the Generalbevollmächtigter für den Arbeitseinsatz – GBA) or at the individual employment offices of the Provincial Fascist Organization of Workers, clear criticisms of the conscription by post of manpower for employment in Germany circulated in the clandestine press prior to the general strike of 1 March 1944 in Bologna. The anti-Fascist press widely read by the workers explicitly equated refusals to report for call-ups to work in the Reich with refusals to comply with the call-up for military service. The effectiveness of the forms of obstructionism adopted was such as to lead RSI authorities to introduce specific punitive measures, targeted at those who failed to report for work when called up (imprisonment of up to 10 years and a fine of up to L. 20,000). Starting in April 1944, the forced transfers to Germany of specialised workers (established by means of company agreements), and of agricultural labour (on the basis of the lists drawn up by municipal commissions), consequently became a source of political conflict between the Resistance movement and the local administration, in the provinces of both Bologna and Modena.

HISTORICAL NOTES

The importance of administrative recruitment by the Italian Social Republic authorities in the Modena countryside.

Attempts at forced recruitment by industrial establishments and the reaction of the Resistance: the strikes of April 1944 in the Modena factories.

The summer of 1944 and the violent recruitment methods in the Apennines. Anti-partisan measures and workforce conscription: from the Wallenstein operations to the Monte Sole massacre.

Caserme Rosse, Fossoli [and Gonzaga], as central hubs for the collection, selection and transfer of forced labourers rounded up from the areas of the front and the Apennines.

by Toni Rovatti