Also in Tuscany, operations aimed at recruiting manpower began shortly after the arrival of the occupiers.

The German and Italian authorities moved on several fronts: first of all, an attempt was made to recruit voluntary workers through an intense propaganda campaign, which envisaged, on the one hand, the mobilisation of trade union organisations and, on the other, the use of posters, flyers, and advertisements in newspapers, as well as recreational events aimed at bringing workers and the unemployed closer together (see the section Local propaganda).

Already in the autumn of 1943, however, there are reports of some roundups of civilians and arrests of anti-Fascist suspects, subsequently sent to the Reich, certainly in the provinces of Florence and Massa Carrara (then Apuania).

From January 1944 onwards the calls for conscription by age group began, while from March onwards conscription was on the basis of lists provided by the local authorities, with the aim of enlisting contingents of various categories of workers, the unemployed, black marketeers and suspicious persons.

There were several reasons for the substantial failure of the recruitment strategies (from October 1943 to May 1944 only about 3,400 people were sent to the Reich): the tendency to avoid military service was widespread, and a substantial number of workers could not be mobilised because they were employed in protected companies or because they possessed counterfeit employment cards. The propaganda and obstacles provided by resistance groups certainly played a role, as they incited the population to boycott recruitment, and on various occasions entered the offices to burn the files and hinder the bureaucratical machine. For example, in Empoli, resistance pressure played a role in the failed conscription of farmworkers. Between March and April 1944, the dragnets carried out in Florence and in the Lucca area had a greater impact, leading to the arrest of “idlers” and alleged anti-Fascists.

From April 1944 onwards, recruitment activity intensified also as a result of the first major anti-Partisan roundups in the Tuscan-Emilian Apennines, which led to the capture of hundreds of civilians, some of whom were sent north. From May-June, the procurement of manpower was combined with operations aimed at slowing down the advance of the front, mainly in two directions: along the coast and the internal Siena-Arezzo-Florence line. The aim of taking as many resources as possible before retreating translated into a widespread strategy of combing the territory in search of able-bodied men. This took place alongside a series of massacres, above all in northern Tuscany, and in particular its western provinces. A conservative estimate indicates that the civilians sent to the Reich amounted to at least 5,000, while tens of thousands more were sent to work locally, in Northern Italy, or released because they were deemed incapacitated; others fled. Among the main collection centres were the Pia Casa di Beneficenza in Lucca and the Scuole Leopoldine near the Santa Maria Novella station in Florence (see the Collection Centres Section).

In the post-war period, while the slow return of veterans posed for the authorities the problem of assistance and the distribution of subsidies to families, some trials for collaborationism included charges of participation in forced recruitment activities and roundups. While amnesty measures would quickly draw a veil over these events, the experiences of civilian internees contributed to the construction of complex local memories relating to the war and the occupation.

Section 1. Local propaganda

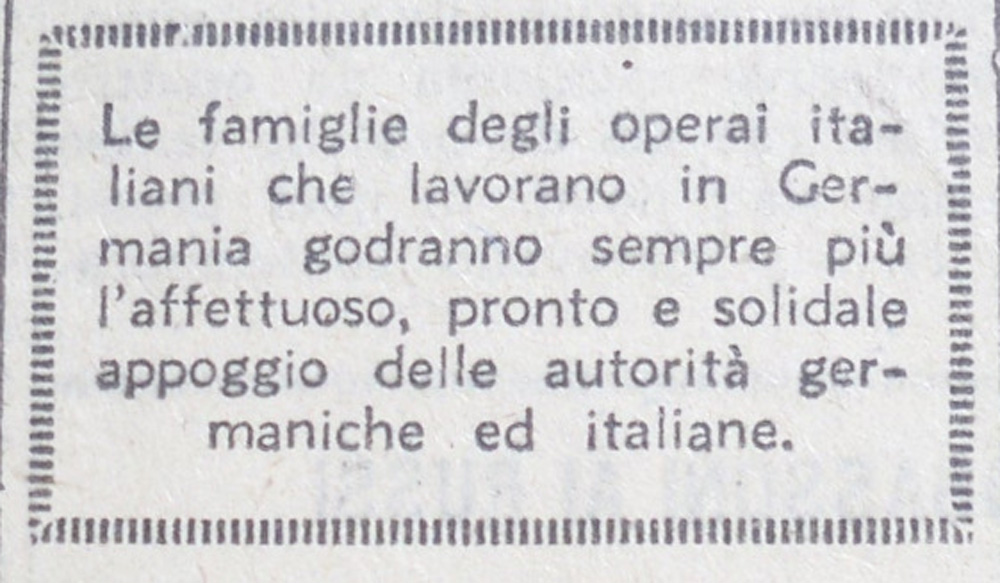

This section contains some images that show how propaganda activities, in which the Italian and German authorities cooperated, did not involve only the distribution of posters, handouts and other material by the central commands to the various regions, but also included initiatives by local newspapers and authorities. These campaigns were intended to counter widespread rumours that living and working conditions in the Reich had drastically worsened after 8 September.

Section 2. Collection centres

Various places in Tuscany were used for the collection and sorting of enlisted civilians. Florence constituted an important hub area, both because many of the workers recruited in the region were taken there, and because convoys from central-southern Italy passed through it. At least from March 1944 onwards the premises of the Scuole Leopoldine in Piazza Santa Maria Novella, a stone’s throw from the station of the same name, was used. The best known place is certainly the Pia Casa di Beneficenza in Via Santa Chiara in Lucca, where in the summer of 1944 the number of inmates probably reached peaks of 3,000; in Carrara, meanwhile, Palazzo Infail and Caserma Dogali were used.

THE HISTORIANS’ VIEW

The results of worker enlistments between autumn 1943 and the spring of 1944.

The role played by the roundups that started in the spring of 1944.

Abduction of forced labourers intensify in the summer of 1944.

The conscription of manpower was combined with the massacres scattered over the region.

by Francesca Cavarocchi