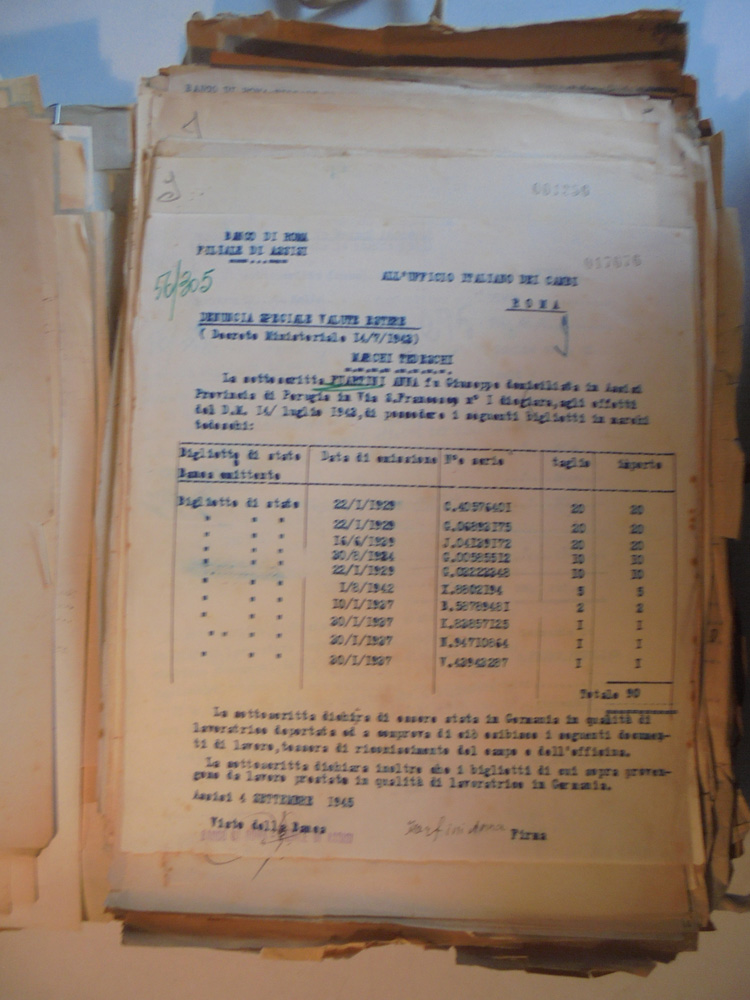

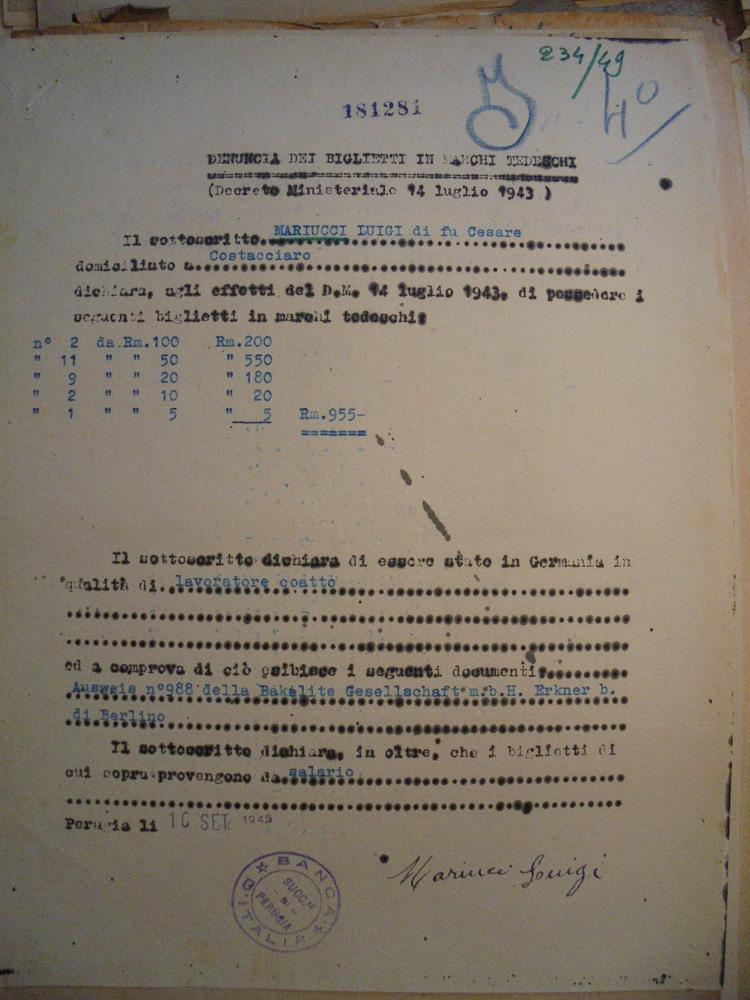

The German occupiers, in sometimes tense collaboration with the Italian Social Republic’s provincial head Armando Rocchi, engaged in massacres, attacks, and shootings, as well as roundups in the areas where partisan brigades operated, in order to provide forced labour for Germany. The individual cases of forced labour shipments would mainly concern rural territories in which at the same time there was also conscription for work, and would affect both the mountain and urban areas of the region. The capillary identification of those refusing to comply with conscription for work in the Reich, by the occupying forces, was aimed not only at identifying members of the resistance but also at establishing the areas where it would then be possible to acquire manpower.

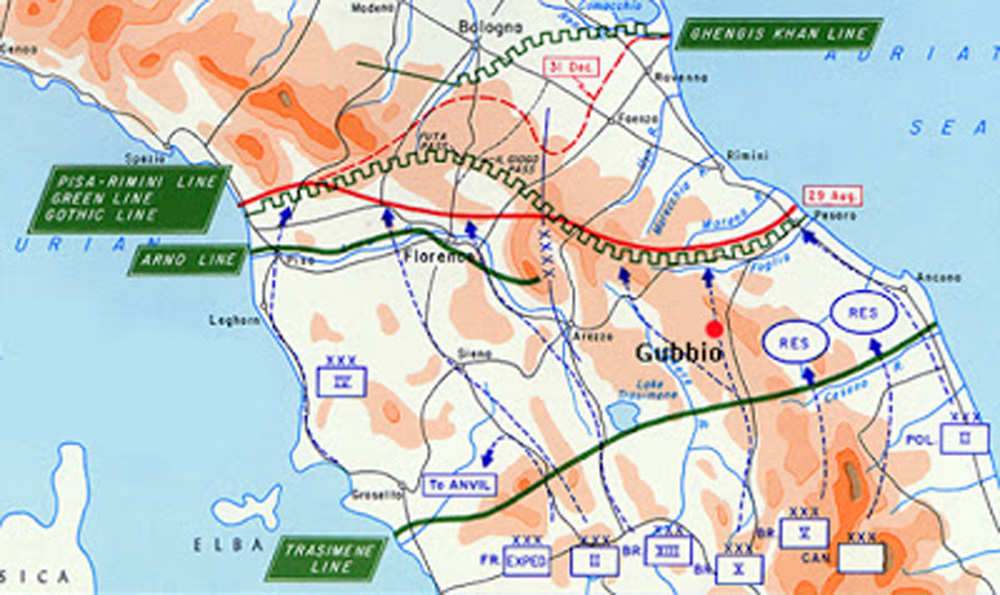

The municipalities and territories that would be directly involved in the region were, in chronological order, the following: Foligno and its province (2 and 23 May 1944) and the Umbria-Marche Apennines (7 May 1944), covering a vast area in the north of the region, and the small towns of San Sepolcro and San Giustino (8 June 1944), as part of operations carried out on the border with Tuscany. These areas had proved particularly difficult to manage in the aftermath of 8 September 1943, since they had seen the proliferation of numerous brigades, groups or bands, constantly engaged in resistance activities. They were all sent to different destinations in the Reich, reflecting Germany’s varied industrial needs and its areas of interest in the war economy. Those captured were above all seen as people who should be uprooted from their place of origin and, at the same time, as manpower to be exploited for German productivity.

An interesting case took place on 30 May 1944, when the Außenkommando in Perugia recorded the arrest of 105 men born in 1914, of whom only 53 would be recognised as suitable for work in Germany at the time of selection.

These men taken from the mountain municipalities, therefore, did not possess the characteristics that usually interested the occupiers, since they were neither partisans, nor specialised workers who could be exploited in the German war industry. They were simply taken to prevent them from potentially joining partisan bands, and at the same time were used as unskilled workers in the Reich.

This last aspect explains why the German authorities were led to assign the Umbrians to various areas that were not solely industrial. Based on the testimonies and archive papers alone, it appears that those arrested were mostly sent to the heavily bombed area of Gdansk. Those rounded up were essentially intended for the removal of rubble and low-skilled jobs.

The effects of the years of war and months of occupation weighed heavily on the industrial and agricultural economy of the region until the end of the 1960s, when only with the recovery of the economic, productive and political system in the area was it finally possible to witness a general and productive improvement.

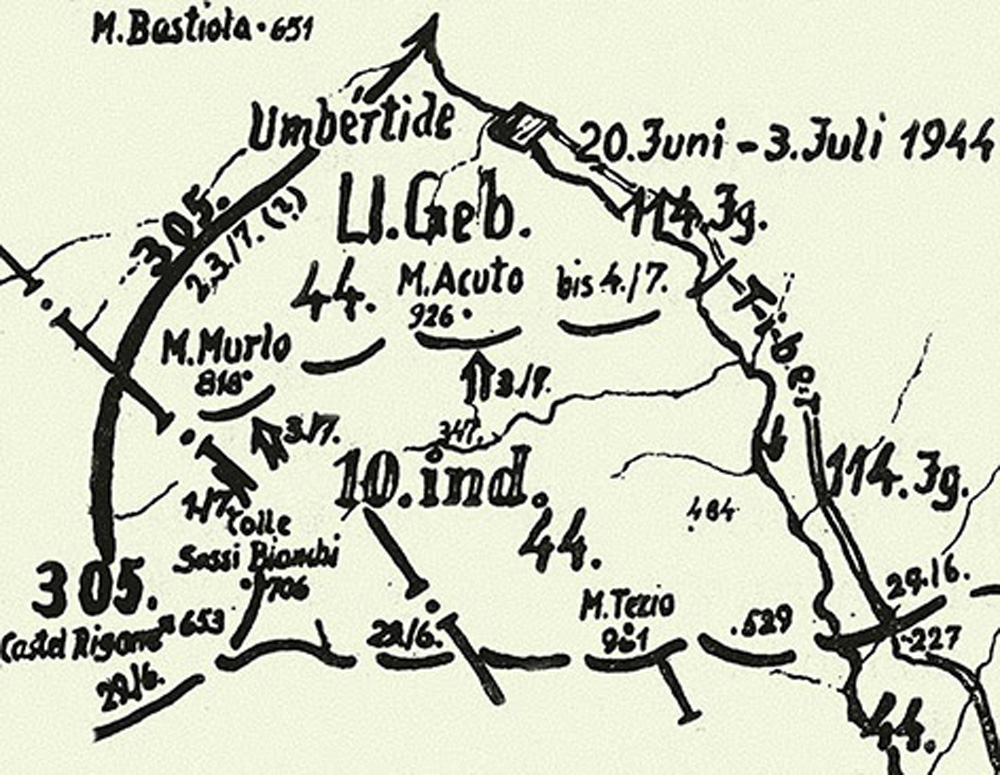

Atlante della Memoria – Alta Valle del Tevere 1943-1944

Interactive map taken from Storia tifernate by Alvaro Tacchini

www.storiatifernate.it

THE HISTORIANS’ VIEW

Why occupying forces in Umbria were unable to take skilled labour from factories after 8 September.

Methods and conditions of the general roundups carried out in retreat. Agricultural labours and farmers in Nazi operations for the Third Reich.

On the front line, working under the bombs. The precarious and difficult conditions In workers’ destinations in the Third Reich.

The role of the Republican National Guard, Italian and German areas of competence, and competition in the round-up phase.

The industrial and human impoverishment of Umbria.

by Antonella Tiburzi