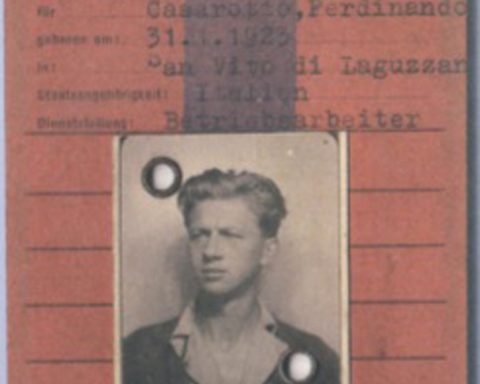

Veneto, where German occupation began on 10 September 1943, was immediately considered a valuable reservoir of manpower to be employed in the territories of the Reich, and later, in the face of a possible Allied advance, in the construction of defensive works locally.

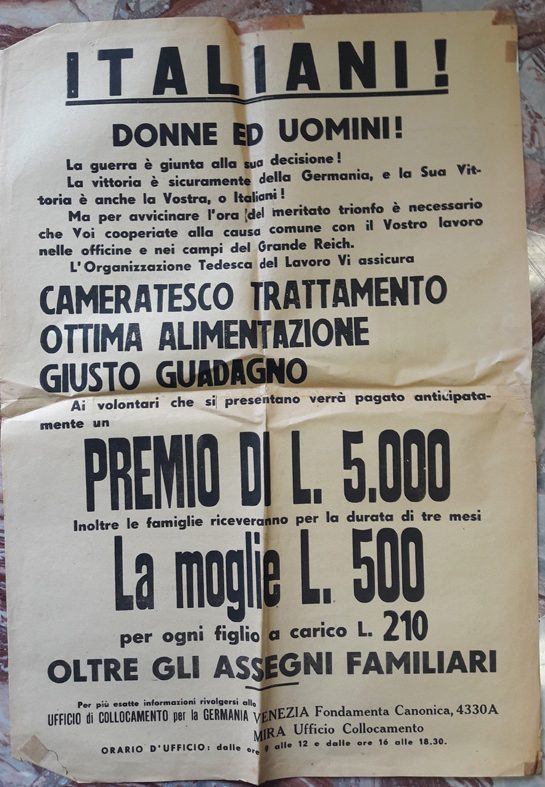

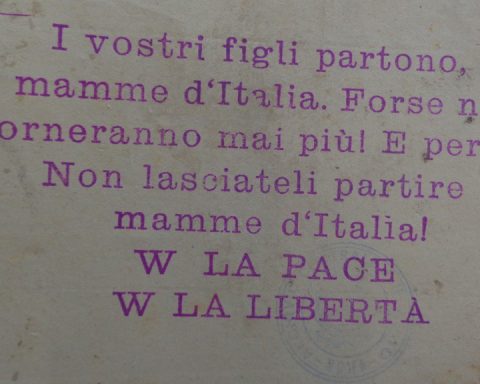

Despite the repeated job advertisements, and working conditions which at least on paper seemed attractive, voluntary applications to move to Germany were extremely rare in all the provinces.

Therefore, having carried out the census, updated several times, of the potential working population, on the basis of the lists prepared by the municipalities and sent to the Employment or Labour Offices, the recruitment of manpower by conscription was adopted. In some areas, for example in Padua, employees took action against the provisions, and the doctors in charge of examining the conditions of the recruited civilians tended to certify them as unsuitable for work in the Reich. Furthermore, some podestà and prefectural commissioners were accused of intentionally compiling lists composed almost entirely of prisoners of war interned in Germany, invalids, workers with family responsibilities and employees in protected industries.

In Polesine, the conscription of female labour for agricultural work gave rise to manifestations of hostility and resistance, with women preferring to be arrested and taken to prison. Elsewhere, armed with sticks, they prevented the men from showing up for their pre-departure medical examinations.

Also in Treviso, “voluntary” recruitment operations, the mobilisation of military service conscripts and the use of other forms of conscription brought in fewer workers than expected: fewer than 500 people in the period between October 1943 and May 1944, including a significant contingent of women, mostly agricultural workers.

The conscription of manpower from the industries of the Vicenza area provoked a series of strikes in March 1944, which ended with agreements between the occupiers and the workers, on the basis of which the forced conscription of women would be suspended. Also in Porto Marghera, the continuous conscriptions of workers were met in the spring of 1944 with strikes. These were repressed with severity, and incarceration, and the subsequent transfer to the Reich’s labour camps or prisons were the most frequent punitive measures.

During the summer of 1944, dragnets and roundups of civilians took place in various areas of the region, allowing the occupiers to recruit a large number of workers to be allocated to neighbouring areas or to be transferred beyond the Brenner Pass; this strategy was combined with anti-partisan repression and involved the cooperation of personnel loyal to the Social Republic.

Finally, there were large-scale operations in the Treviso and Venice areas by Organisation Todt and the RSI’s Labour Battalions for the recruitment of forced labour for use locally in the construction of anti-tank trenches and other defence systems.

by Francesca Cavarocchi, Adriana Lotto and Sonia Residori