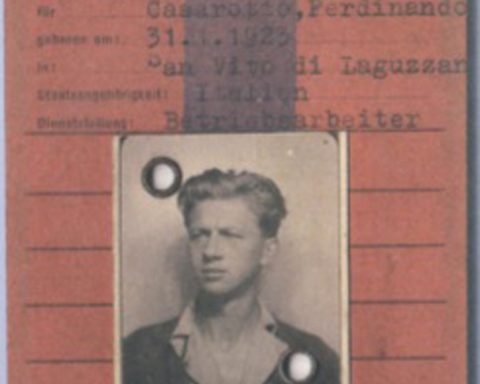

After a clumsy attempt to transfer entire families to the lands of the Reich for agricultural work, on 19 February 1944 the prefect Federico Menna ordered all the municipal heads, the podestà, and prefectural commissioners of the province of Rovigo to submit by 10 March the lists of those who could be drafted into work in Germany, without distinction between men and women.

The intention was to leverage the traditional industriousness of the Polesine people to make recruitment as voluntary as possible, but given the decidedly insufficient response, all citizens, regardless of social status, were conscripted.

“Workers” was intended as meaning not only manual workers, but also those employed in commercial, industrial and agricultural activities, with the exception of company managers, but only one per company.

The names had to be provided by the municipal commissions made up of the podestà or prefectural commissioner as chairman, the secretary of the local Republican Fascist Party, the commander of the local GNR, and the town council employment officer, with the cooperation of all the local representatives of the workers’ trade unions and employers.

In reality, since they were all members of the communities, no one wanted to take responsibility for reporting the names, so the lists had been compiled in a very approximate way, as Prefect Menna complained, so much so that the Employment Office had to redo all the work, wasting a considerable amount of time.

In any case, the local authorities, although part of the Fascist institutions, wanted nothing to do with what was perceived as a violent attack on family life [1 – ASRo, Prefettura, b. 951, Commissione provinciale di censura – 27 marzo 1944].

On 7 March 1944, in Trecenta, after insistent persuasion, they had managed to get 75 workers to leave for Germany, but neither the podestà, nor the secretary of the Fascist party, nor any other public authority showed up at the time of the departure of the conscripted workers. There were harrowing scenes of crying, screaming and fainting, but also of animosity towards the authorities.

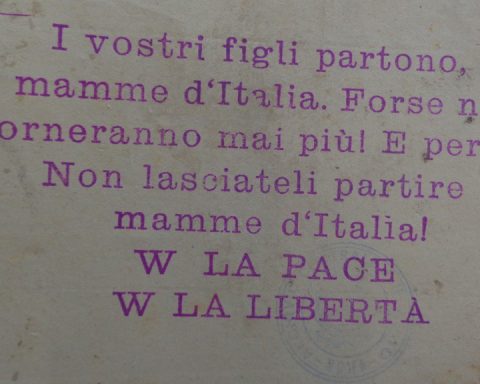

Also in the Polesine the conscription of women aroused widespread hostility and resistance. In some cases, such as Trecenta, the women preferred to be arrested and taken to prison on charges of refusing to receive call-up papers for Germany [2-4 – ASRo, Prefettura, Gabinetto, II vers., Atti segreteria particolare, a. 1944, b. 49].

In Crispino, on the other hand, large numbers of women first took to the streets to protest and then, threatening and armed with sticks, prevented the men from presenting themselves for their pre-departure medical examination. In this way, the men were seen to be willing to obey higher orders and, consequently, could not be charged or arrested. The protest lasted until mid-April, when, in Pettorazza, hundreds of women demonstrated against the sending of relatives to Germany [5 – ASRo, Prefettura, Gabinetto, II vers., Atti segreteria particolare, a. 1944, b. 49, fasc. 3; 6 – ASRo, Prefettura, Gabinetto, II vers., Atti segreteria particolare, a. 1944, b. 49, fasc. 24].

The news reports of the Republican National Guard noted that conscription had given poor results throughout the province: in the early days of March the municipal commissions had managed to recruit 7,000 workers, both men and women, and it was therefore necessary, on the one hand, to increase the penalties, in terms of fines and prison sentences, and on the other to proceed with conscription by age group.

The previous lists were joined by others, now compiled in great secrecy, of persons considered subversive, but also of Fascists whom it was considered prudent to dispose of. There were also public lists including former carabinieri, habitually “idle” individuals, those suspected of trafficking on the black market, and anyone whom the new Fascist state might not appreciate or was an obstacle to the continuation of the war being waged [7 – ASRo, Prefettura, Gabinetto, II vers., Atti segreteria particolare, a. 1944, b. 49, fasc. 24].

Conscription met with significant setbacks and difficulties, so the Republican National Guard carried out at least 18 house-by-house roundups between April and May 1944, mainly at night to catch workers unwilling to go to Germany in their sleep. A few dozen people were captured, but many conscripts had by now joined the partisans [8 and 9 – 6 – ASRo, Prefettura, Gabinetto, II vers., Atti segreteria particolare, a. 1944, b. 49, fasc. 24].

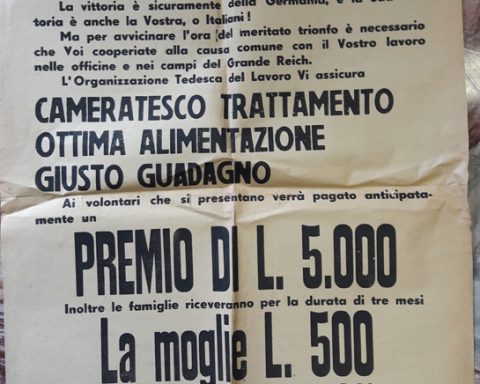

In order to encourage people to go and work in the Reich, the Italian authorities and the German agencies sent to Italy for recruitment published a series of advertisements in Rinascita, the weekly of Rovigo’s Federation of Republican Fascists, which tried to capture readers’ attention through promotional messages.

The appeals were addressed to the entire population aged 16 to 60, and to those in every trade, from farmers and barbers, to chicken farmers and engineers.

The promises were always the same: high wages, assistance, protection, and absolute equality with German workers. The requests to move to Germany, similar to advertising slogans, adopted an affable, almost confidential tone, whereby “father”, too formal an appellative for a parent, became the sweeter “Dad” (babbo): “Dad’s working for us in Germany!”, the little girl exclaims happily at the sight of the wad of large banknotes her mother is waving in front of her [10 – Rinascita 2 luglio 1944 (ASRo, CAS, b. 1, fasc. 4); 11 e 12 – Rinascita 5 agosto 1944 (ASRo, CAS, b. 1, fasc. 4); 13 e 14 – 13 – Rinascita 9 luglio 1944 (ASRo, CAS, b. 1, fasc. 4); 15 – Rinascita 18 giugno 1944 (ASRo, CAS, b. 1, fasc. 4); 16 – Rinascita 19 agosto 1944 (ASRo, CAS, b. 1, fasc. 4); 17 – Rinascita 19 marzo 1944 (ASRo, CAS, b. 1, fasc. 4); 18 – Rinascita 21 gennaio 1944 (ASRo, CAS, b. 1, fasc. 4); 19 -Rinascita 13 febbraio 1944 (ASRo, CAS, b. 1, fasc. 4)].

THE HISTORIANS’ VIEW

The reaction of the Polesine population to coercive labour measures.

The measures taken by the German and Italian authorities in the face of low numbers of volunteers prepared to work in Germany.

The means used to encourage people to go to Germany.

by Sonia Residori