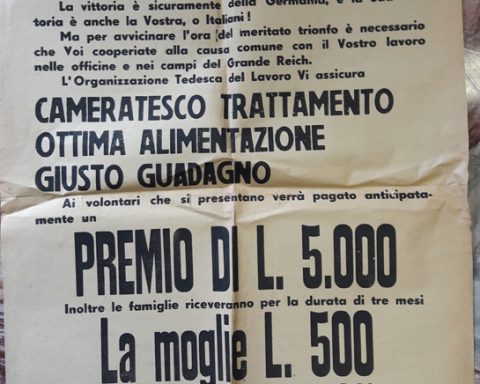

Since November 1943, notices for the voluntary enlistment of Italian workers for the Reich had appeared repeatedly in local newspapers in Padua, and brightly-coloured posters were posted on the walls, reporting the great advantages offered to those who agreed to go to work in Germany: high wages, excellent treatment, payment of part of the salary to families in Italy, salary bonus paid upon crossing the border; equipment allowance, doubled family allowances, severance pay, and life insurance.

The task of recruiting voluntary workers for the Reich was entrusted to the “Group for the employment of manpower”, an office located in Padua in Via San Francesco 19, part of the Militärkommandantur 1004, while a “Workers’ Recruitment Office for Germany” was opened in Via Luigi Razza (now Via del Carmine).

On 1 February 1944, the “Regulations for compulsory labour service” were issued for all male citizens eligible for military service born between 1899 and 1926, of whom the appropriate municipal commissions had to compile lists [ASPD, Prefettura Gabinetto, cat. V, Corporazioni e Associazioni sindacali 1943-1945, b. 565].

The focus was on voluntary transfers to Germany, but the large number of workers required per town, defined as “absurd” and then “impossible”, was unlikely to be achieved on a voluntary basis [2 – ASPD, Prefettura Gabinetto, Cat. XXII, Affari vari 1943-1945, b. 601, fasc. 33].

The pressure to which the municipal authorities were subjected would require them to make more or less veiled threats, and adopt more or less heavy-handed persuasive methods, to the point that in some municipalities in the province of Padua the members of the municipal commissions failed to attend the meetings, and in some cases to send call-up papers. [3 – ASPD, Prefettura Gabinetto, Cat. XXII, Affari vari 1943-1945, b. 601, fasc. 33].

At the same time, there was widespread propaganda against the obligation to work in Germany, with the distribution of many leaflets, clandestine newspapers and wall posters inviting workers not to report for duty, or to refuse to sign for the delivery of call-up papers [4-8 – ACS, MI, Dgps, Dagr, Rsi 1943-1945, b. 14, fasc. 34/1 – Padova 1944; 9 – ACS, MI, Dgps, Dagr, Rsi 1943-1945, b. 14, fasc. 34/2 – Padova 1944].

In Casalserugo, however, unknown people threw bombs, which did not explode, against the house of the Fascist commissioner to protest against conscription.

Given the extreme lack of interest from workers, the Ministry of the Interior of the Italian Social Republic considered forcing prison inmates to work, but in Padua an initial selection ended with just 14 men being sent to Germany [10 – ACS, MI, Dgps, Dagr, Rsi 1943-1945, b. 14, fasc. 34/3 – Padova 1944].

Towards the end of March, the GNR – Carabinieri Group of Padua forwarded two lists of “undesirable elements”, i.e. of unemployed people considered idle and vagabonds, divided by municipality, for a total of 267 names. [11 – ASPD, Prefettura Gabinetto, cat. V, Corporazioni e Associazioni sindacali 1943-1945, b. 565]

The operation had been carried out at the orders of the Single Employment Office, a joint Italian-German office set up in that period, with the task of systematically ensuring achievement of the recruitment goals.

But the Italian employees showed little inclination to cooperate, partly because they did not want to assume responsibility for the unpopular measure of sending workers to Germany by force, partly because they probably had links to the Resistance [12 – ASPD, Prefettura Gabinetto, cat. V, Corporazioni e Associazioni sindacali 1943-1945, b. 565].

On 1 May 1944, dissatisfaction with the Italian offices was reported: while the labour police played an active role In operations, albeit in small numbers, the director of the employment office in Padua was dismissed for “sabotaging” German instructions, as were the doctors in charge of assessing the conditions of recruited civilians, who tended to certify the latter as unsuitable for work in the Reich.

The Germans accused the podestà and the municipal prefectural commissioners of intentionally compiling excessively long lists of workers to be recruited for the Reich, lists which upon checking were found to be composed almost entirely of prisoners of war interned in Germany, invalids, workers with family responsibilities or employees in protected industries.

Faced with people’s lack of interest in going to work in Germany, local roundups began in Este, Montagnana, and Monselice, causing workers in the area to down tools, and some to go into hiding.

In any case, local newspapers gave almost daily reports, clearly for intimidation purposes, of the arrests of those dodging labour conscription.

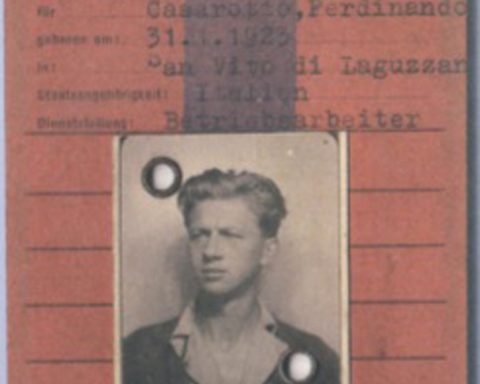

A document drafted by the Provincial Employment Office, dated 11 April 1945, stressed that the workers who had moved from Padua to Germany before 8 September 1943 numbered 29,054, and after that date 1,590, even if the provincial director had to admit that not all had moved there of their own accord [13 – ASPD, Prefettura Gabinetto, Cat. XXII, Affari vari 1943-1945, b. 601, fasc. 33; 14 and 15 – ASPD, Prefettura Gabinetto, cat. V, Corporazioni e Associazioni sindacali 1943-1945, b. 565].

THE HISTORIANS’ VIEW

The criteria that guided the local authorities in compiling the lists of individuals to be conscripted for work in Germany.

Hostility or boycotting of Italian authorities towards the German conscription of the workforce.

How many workers were forced to move from Padua to the Reich?

by Sonia Residori