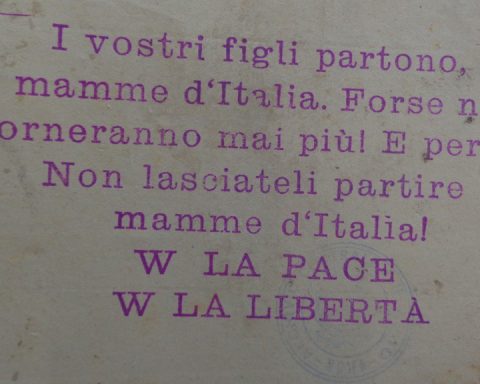

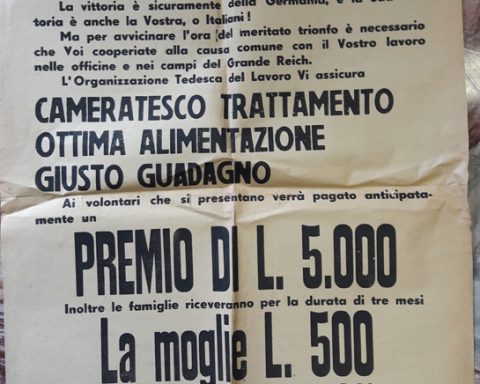

In the Vicenza area, starting from mid-February 1944, call-up papers for work in Germany were sent to male and female workers, leading to deep malcontent. The situation precipitated with the call for medical examinations, so much so that the companies in the Vicenza industrial areas began to strike in succession, first in Schio and then Valdagno. With the widening of the protest, “subversive” flyers were distributed everywhere, in particular opposing the recruitment of women for work in Germany. This was seen as a moral offence, since – it was argued – in the Reich, they would be exposed to both physical and moral dangers, and would risk becoming easy prey for German soldiers. The rumours that circulated painted a dire picture of what awaited conscripted women, so much so that many of them had already planned their escape [ 1 – ACS, MI, Dgps, Dagr, Rsi, 1943-45, b. 20, fasc. 62/1, Vicenza manifesti e stampa sovversiva 1944; 2 – ACS, MI, Dgps, Dagr, Rsi, 1943-45, b. 20, fasc. 62/2, Vicenza manifestini sovversivi 1944].

Faced with the workers’ unrest and popular malcontent, the methods of repression adopted by the Fascists became increasingly treacherous, and were made worse by the German military authorities, which adopted severe reprisal measures, for the moment only limited.

In particular, however, the workers of the Officine Pellizzari of Arzignano were targeted; they went on strike on 28 March 1944 against labour conscription. As a result, four workers were executed in the hills of Montecchio Maggiore, while 24 were imprisoned and then taken to the Fòssoli concentration camp [3, 4, 5 – Archivio privato De Marzi, Corrispondenza Fossoli].

Of these, 21 were deported to Mauthausen, in shipment no. 53, even if they then followed different paths. Costantino Zini and Giuseppe Rampazzo remained in KL, in Mauthausen and Gusen; the former died shortly after returning home, and the latter in the camp on 10 January 1945 at 5.40 in the morning, as reported in the Todesmeldung [6 – Arolsen Archives – 1710427 Giuseppe Rampazzo; 7 – Arolsen Archives – 130143152 Costantino Zini].

The others, meanwhile, after signing a commitment to “good behaviour”, were sent to work in the various factories of the Reich. Romeo De Marzi worked for Kraftwerke Oberdonau in Gmunden and for Aluminumwerke GmbH in Steeg am Hallstättersee [8 and 9 – Archivio privato De Marzi, Arbeitsbuch für Ausländer ; 10 and 11 – Archivio privato De Marzi, Kontrollkarte für den Auslandsbriefverkehr].

I have sent you 300 Lire, he wrote to his wife on 8 September 1944, to reassure her, and I am sure you will receive it. If you don’t need it you can buy a small high chair for Gabriella, at least as a memento of her father from Germany […] work is going very well, Saturday after lunch and Sunday we party, I’m not having any problems with the food, a caffè latte in the morning, at noon I eat in the refectory and in the evening I prepare something myself. I eat about 500 g of bread with salami, butter or margarine or jam with sugar and then I go and have a bowl of soup and a good beer [12 – Archivio privato De Marzi, Corrispondenza Steeg].

Despite the strikes, conscription for work in Germany continued, also involving the workers of the large Vicenza factories, but the issue of women workers was shelved. On 17 April 1944, the secretary of the Republican Fascist Party, Alessandro Pavolini, informed all the provincial heads that the conscription of women was suspended, preferring, especially for peasant women, to focus on voluntary requests to go and work in Germany.

On 8 May, 80 Marzotto workers, divided into two groups, were forcibly transferred: one group arrived at the destination of Maltheuern/Brüx (Most), in the Sudeten region, and was employed at the Sudetenländische Treibstoffwerke A.G.; the other was sent to the town of Vorwohle, 20 km from Holzminden, in Lower Saxony, and was employed at the Portland Cement Fabrik [13 and 14 – Archivio privato Cracco, Diario; 15-18 – ACVa, b. 525, 1944, fasc. Mobilitazione per lavoro obbligatorio]

Giovanni Cracco wrote a diary of the experience – conscription, forced transfer and life in the factory, while a letter written by Igino Spiller to his family members in August 1944 remains among the papers in the municipal archive:

Vorwohle 16-8

Dear dad and brother

I am writing this letter to let you know I am in excellent health, and hope that you too and all my siblings far away are also well. I have no news to tell you, life is always the same here. I haven’t received any mail from you yet, the last letter I received was the one about the papers. On the subject of those papers, I’m not entitled to anything; the family distance allowance is only for married couples. I still haven’t received any mail from my siblings; I hope you’re receiving mine. I wrote to Maria Catinella Ida and others and after being here for three months I’ve only received 3 letters from you. Are the letters not arriving or are they all dead? I hope not. Anyway, say hello to them all. As I wrote to you on another postcard, I sent you 100 marks, I hope it arrives. Greetings to Cleto, if he is still in Vicenza, Rino, Giovanni and the girls. Say hello to the Lora family. I have nothing else to tell you. Keep up your spirits, hope to see you soon, goodbye for now, your loving son and brother

Igino

I have just received a letter from Cleto from Ravenna dated 27.7. He’s well.

[19-20 – ACVa, b. 525, 1944, fasc. Mobilitazione per lavoro obbligatorio].

The Resistance movement immediately reacted against labour conscription, organising high-profile and at times violent operations. In Valdagno, the municipal janitor, in charge of delivering call-up papers to homes, was captured by a partisan patrol and released after being told to busy himself with other work, or be killed.

On 12 June 1944, while a group of about twenty young men from San Vito di Leguzzano were being escorted to Schio by Fascist militias, partisans hidden behind hedges on the sides of the road attacked the escort, engaging in an exchange of gunfire which intensified with the arrival of German reinforcements [21-22 – APSVL, Cronistorico 8.VI.1944].

Some of the young partisans escaped, but in the end almost all of them were captured and first sent to prison in San Biagio, Vicenza, and then to work in Germany. Ferdinando Casarotto, for example, was sent to the same factory as the workers from Valdagno, the Sudetenländische Treibstoffwerke in Oberleutensdorf (today Litvínov) – District of Brüx; Luigi Bertoldi to the 11a Wohnlager 31 über Brüx as an electrician. Others, such as Umberto Sette and Giuseppe Veronese, were sent to Salzburg, respectively as a mechanic and train driver [23 – Archivio privato Casarotto, Werksausweis di Casarotto Ferdinando ; 24 – APSVL, Foto dei reduci con il parroco, don Fracca, 1946].

THE HISTORIANS’ VIEW

Conscription for forced labour in Germany led to discontent, protests and strikes in the major industries of Vicenza.

The repressive measures adopted by the German occupation forces against workers at the Pellizzari plant.

The reaction of the Resistance to conscription of the workforce.

by Sonia Residori