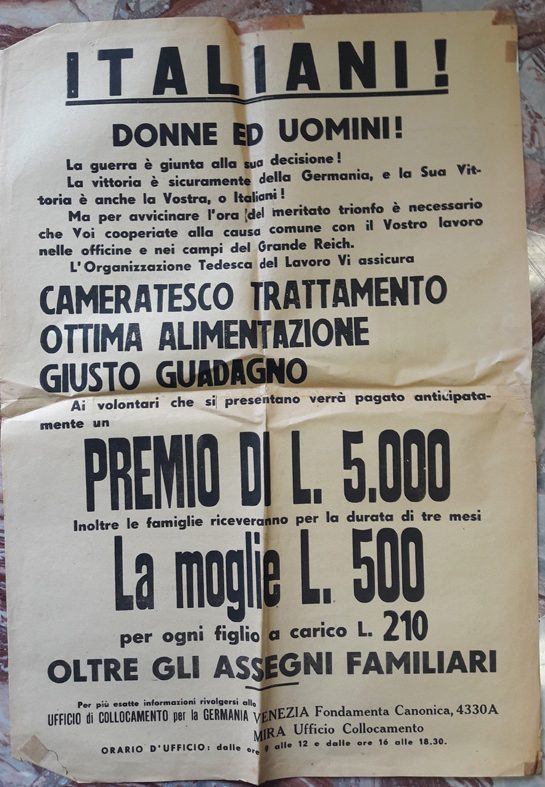

The Italo-German agreements of 1937-38 regarding the sending of Italian workers to Germany offered a solution to the serious employment situation in Venice and the provinces, with the result that in 1940 the industrial workers present in the Reich already numbered 2000.

On 12 September 1943 Venice and the surrounding area were occupied without resistance by the German troops. On 15 September an initial notice was issued which, among other things, ordered officers, excluding those who had already enlisted in the Wehrmacht, to report to the “Terminus” and “Germania” hotels by 8 pm on the same day. A second notice, dated 18 September, instead obliged everyone, NCOs and the rest, excluding those on leave or who had already enlisted in the Wehrmacht, to report to the “Danieli” Hotel. Many remained in hiding, but others ran into dragnets or roundups, and large numbers would later be sent to forced labour in the Reich, especially (but not only) in Austria. Quite a few showed up for fear of retaliation, but arrived late, and soon fled, as recounted by Renato Lazzarini, born in Venice on 13 October 1924. Once recaptured, they were taken to the prisons of the Reich and sent to forced labour: “And there we encountered the German SS and the black Fascist brigades, who lined us up and escorted us under armed guard into the wagons waiting at the station to take us all to Germany. From here began my forced pilgrimage across the whole of Germany, Prussia and Poland.”

The soldiers and veterans were joined in the spring of 1944 by those called up for labour service, including the workers of Porto Marghera born in 1911 and 1914, and those who would go on strike against the continuous conscription of manpower.

Despite the massive propaganda action, at the end of March 1944, out of a total force of 9,041 young men born between 1922 and 1925 obliged to report for duty, the dodgers amounted to about 3,000. By way of response, the authorities began to arrest family members in their place and sent them to the Reich as forced workers. A case in point was Pietro Penso, a shopkeeper from Cannaregio, born in 1897, who was arrested on 15 August because his son Sergio had not reported when called up. Taken to the prison of Santa Maria Maggiore and placed at the disposal of the RSI Employment Office, he was handed over to the occupants who sent him to Sankt Valentin, in Lower Austria, where he arrived on 1 September.

On 18 March the following year he would write to his wife: “My dear Antonietta, no post or parcel today either, but I hope you are all in good health as I can assure you of myself. I was so hoping for a package to arrive, so at least I could have some food, since I’m a bit short and don’t know when I’ll be able to get back on track. Tomorrow or later I will write to you at length, since tomorrow I go on duty at night and I have a little more time during the day. Life is always the same here and everyone hopes it will change, otherwise we’ll all really be in trouble; I hope that Renato and Gastone have written to me; I wrote to them. I’m sending you three lots of kisses and love and another big big kiss, your husband”.

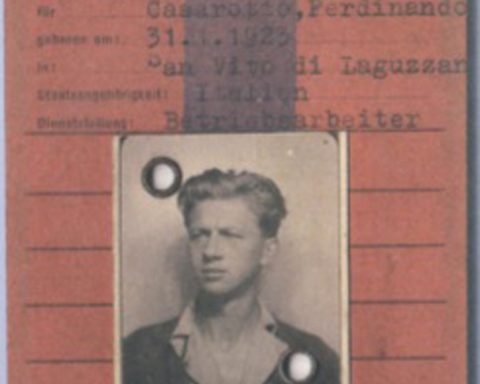

Those in prison for common crimes or crimes against public order and the draft dodgers were also subsequently handed over to the Employment Office or to the German Police, and sent as forced workers beyond the Brenner Pass. Some suspected of engaging in anti-Fascist activity were also sent to the Reich for forced labour, perhaps because they were skilled workers. Such was the case of Gino Viviani, born in 1917, originally from Donada (in the province of Rovigo). Dismissed on 12 March 1944 from Montecatini di Marghera because he was conscripted for forced labour, he was arrested on 27 March as an anti-Fascist suspect by the Mestre police and taken with other forced workers first to Schärding am Inn in Upper Austria to the Hans Lutz company, and later to Oberschlesische Hydrierwerke in Blechhammer, in Upper Silesia, employed by the same company, as an electric welder.

In the summer of 1944, the roundups and arrests, often carried out by the Black Brigades, and the consequent conscription of workers, were the response to the acts of sabotage carried out by communist groups.

All those arrested who were placed at the disposal of either the Employment Office for transfer to the Reich, or of the SS, which arranged to transfer them to the Reich’s prisons, passed through the Venetian prisons of Santa Maria Maggiore.

Giuseppe Maura, born in 1903, and Guido Dalla Venezia, born in 1913, arrested together on 24 August and placed at the disposal of the SS, were sent to Austria on 23 September. Maura would be employed as a carpenter at the Shell refinery in Floridsdorf (Vienna), which after the Anschluss depended on its German subsidiary, Rhenania-Ossag. Dalla Venezia, on the other hand, would be sent from Innsbruck to the Sudetenland.

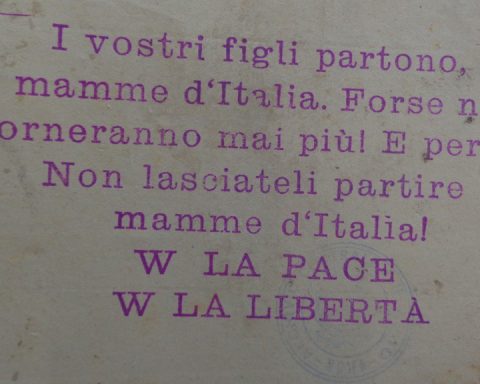

In the early days of May 1944, also following the strikes of March and 1 May, numerous workers born in 1911-1914, conscripted and abducted from Porto Marghera, were immediately packed into sealed wagons and sent off to Germany. On 8 May, the workers went on strike in large numbers. This was encouraged by the Venetian Communist Federation and the port’s internal rebel committee, with leaflets expressing the appeal: “Workers! We must strike to resist the cynical Nazi-Fascist’s intentions to make us die in Germany. Stop the deportations to Germany”

However, it was above all in the summer of 1944, when the sabotage operations targeting production and communication routes intensified, that more arrests and transfers to the Reich were made, also because, despite the massive recruitment campaign, no one wanted to go to work in Germany. Moreover, the Militärkommandantur 1004, based in Padua and on which Venice depended, wrote in its report: “Enormous difficulties in recruiting manpower for Germany. The repatriation of sick Italian internees from the Reich to Italy (early June) had a very unfavourable effect on the popular mood, since the majority believed that all Italians in Germany were treated badly and that they fell ill there”. This was also admitted by Giorgio Pini, undersecretary of the Interior of the RSI in the report on his inspection of 21 and 22 November: “In the Mestre-Marghera area, hard hit by bombing, only 25 percent of the factories are still operational. Raw materials are scarce, especially coal, so that unemployment is foreseen in the near future, aggravated by the fact that the workers do not want to go to Germany”.

In any case, above all skilled workers (mechanics, naval mechanics, carpenters, glassmakers) would be taken from the historic centre of Venice, from Mestre and from Marghera, while in the autumn of 1944, 20,000 men of all ages and professions were rounded up in the municipalities of the mainland and employed locally in building earthworks and digging anti-tank trenches, with the aim of blocking a possible Allied landing, considered highly probable by the high commands of the Wehrmacht until spring 1945 (contemporary German military maps refer to “Fall Grete” = Genoa; “Fall Luise” = Livorno, and “Fall Cecilie” = Chioggia).

For more information, see the accompanying images and captions; the material comes from the Archivio di Stato di Venezia (ASV), the Archivio Generale del Comune di Venezia (AGCV), the Archivio dell’Istituto Veneziano per la Storia della Resistenza e della Società contemporanea (AIVESER) and the Archivio Storico del Comune di Mirano (ASCM)

THE HISTORIANS’ VIEW

The employment crisis in Venice in the 1930s and the first emigrants to Germany in 1938.

The strikes in Porto Marghera and labour conscription.

The sorting of skilled workers sent to Germany and general labour for the construction of defence works in the Venice area.

by Adriana Lotto